History

Company history

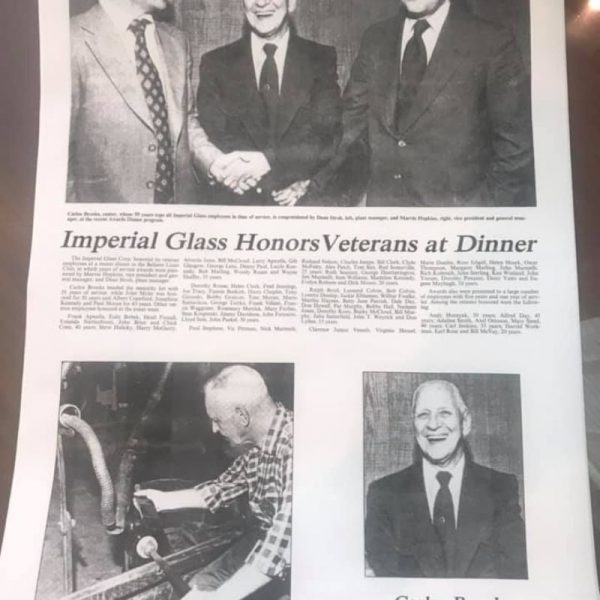

The story of Imperial Glass is one that could be told by recounting the plethora of glass patterns that Imperial manufactured during 80 years of production. However, it is the men and women of Imperial who charted Imperial’s course beginning in 1901 that bears repeating. It is a journey navigated through calm waters, turbulent currents, and literally, floodwaters. It is a tale of vision, innovation, ambition, intrigue, and a determination to succeed. Further, it is a key part of the history and heritage of Bellaire, Ohio and the Upper Ohio Valley.

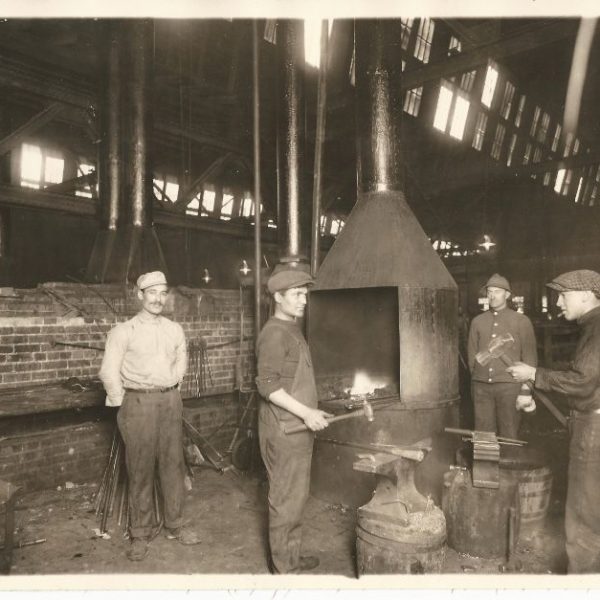

The American handmade glass industry was no stranger to the Ohio Valley at the turn of the last century. Abundant, low cost energy resources, excellent river and rail transportation, and a ready work force made it possible for numerous glass manufacturers, both large and small, to prosper.

Imperial’s story begins with Edward Muhleman, a former Wheeling riverboat captain and financier, and his entanglement with the National Glass Company. That combine formed late on Friday night, September 8, 1899 at Newell’s Hotel in Pittsburgh, Pa.; it absorbed, among others, Captain Ed’s Crystal Glass Company of Bridgeport, Ohio. Less than two years later, he apparently became disenchanted with the National Glass Company combine. He was an effective manager, and although wealthy, he was not ready to retire. Further, he had a fascination with the glass tableware business. Thus, he decided to build from scratch a new, large, independent glass company in Bellaire, Ohio.

With assistance from the Bellaire Board of Trade and several of his former Crystal Glass Company stockholders, Muhleman commenced to turn vision into reality. He acquired land, raised capital, hired employees, and secured a charter. By December 1901, the new entity had become the Imperial Glass Company—displacing the original “New Crystal” name. On December 11, 1901, stockholders gathered at the Belmont Savings and Loan on Union Street in Bellaire and formed a board of directors that consisted of eight Wheeling residents and one Bellaire resident. The following day, the board elected J. N. Vance of Wheeling as Imperial’s president and Ed Muhleman of Wheeling as Secretary. Just days later, Mr. Muhleman took occupancy of Imperial’s first office. It was located on the first floor of the First National Bank of Bellaire located at 3200 Belmont Street—the exact location of the property owned by and adjacent to the current National Imperial Glass Museum.

In 1902, Captain Ed hired Victor G. Wicke of New York City as Secretary. When Ed was managing Crystal in Bridgeport, Wicke operated a very successful showroom on Park Place and was an agent for Capt. Ed and Crystal Glass. The two had a great working relationship. On Monday, August 11, 1902, Wicke completed purchase of the Fred Seabright property at 4711 Guernsey Street in the Gravel Hill (northern) section of Bellaire. He resided there until his passing in 1929.

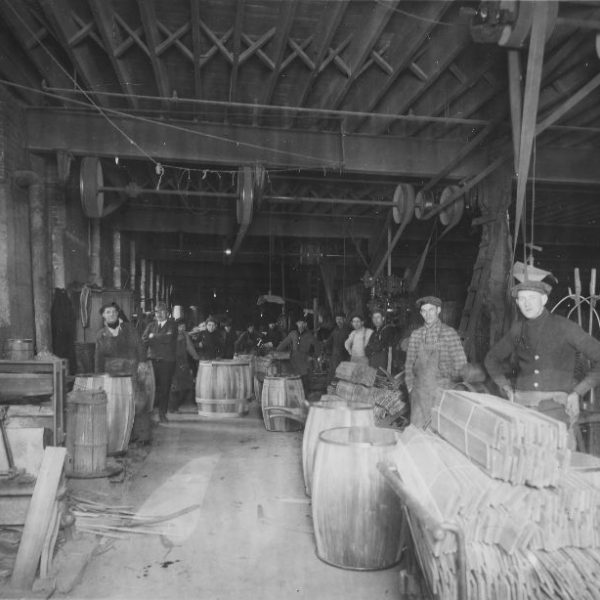

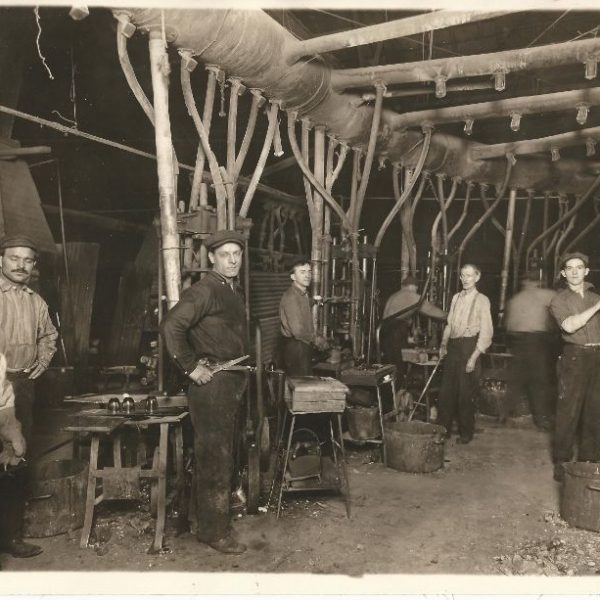

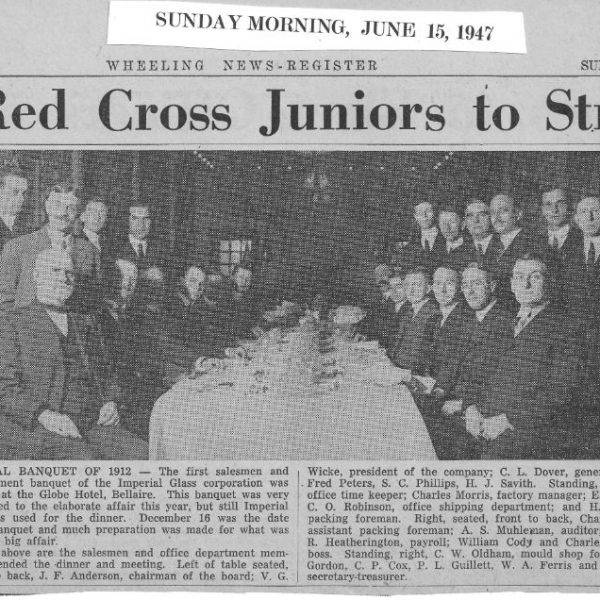

The building process was slow; the Company encountered a myriad challenges, setbacks, and shortages of all sorts. As 1903 wore on, everyone waited and watched for activity at the new “Big Imperial” plant in Bellaire. By October, it appeared that production was imminent. Imperial had orders, employees, moulds, and a nearly functional glass house. Finally, the Wheeling Intelligencer reported that production began on Wednesday, February 3, 1904.

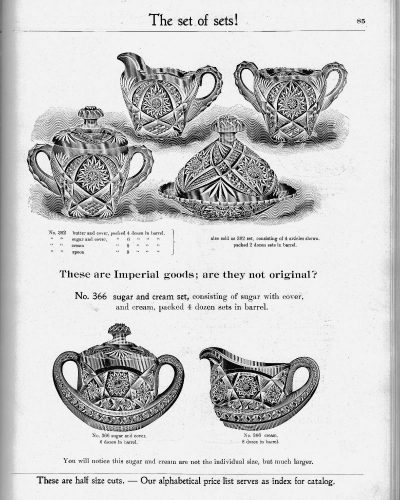

Amazingly, within six months, Imperial became a major player in the handmade glass industry. The upstart “Big Imperial” turned out all manner of bottles, tumblers, jelly jars, electric and gas lamps, and no less than fifteen full lines of tableware. Imperial priced its intricate, press-moulded patterns over a broad range, thus enabling the company to reach a wide customer base. It offered higher quality pot glass, referred to as “mirror glass,” along with utility glass produced from a continuous-feed melting tank.

Victor Wicke was largely responsible for Imperial’s early success. He possessed the energy, creativity, and resourcefulness that enabled him to consummate a deal in 1904 with F. W. Woolworth and its some 500 stores. Faced with the task of finding markets and customers for the plant’s rapidly increasing production capability and new lines, Wicke was more than up to the challenge. Other retailers such as McCrory and Kresge soon carried Imperial glassware. Later, Butler Brothers and other major wholesalers joined in the prosperity of Imperial.

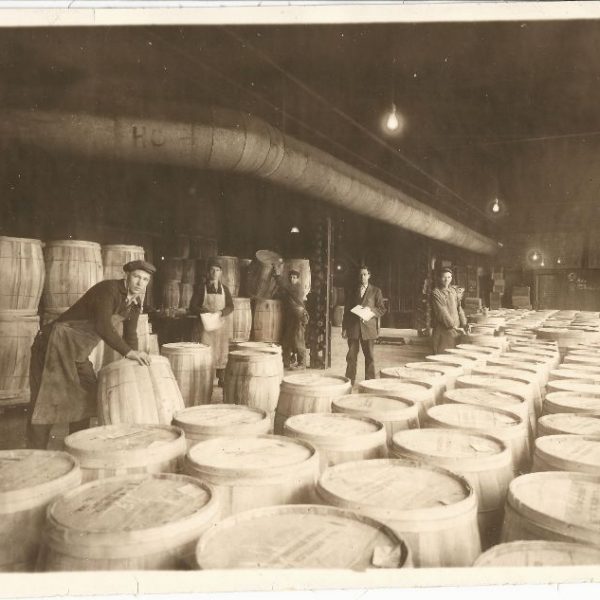

Wicke’s marketing creativity found new ways to attract buyers to Imperial glass. His strategy for Imperial took radical turn in January 1906 when he opted out of the traditional Pittsburgh Glass Show. Instead he invited the buyers to come to Bellaire and see the plant in person. By year’s end, the huge plant was producing at near capacity. Employing hundreds of highly skilled glass workers, Imperial’s wide range of glassware and sheer volume of production had caught the attention of the entire industry. 1909 saw Imperial make its first foray into colored glass items. A trade journal of the period reported that at the end of 1909 Imperial had sold 50,000 more barrels of glass than it had the year before! By 1910, Edward Muhleman had realized his dream; he sold all of his stock and retired. Victor G. Wicke then became head of the “Big I.”

In the decade of the 1910s Earl Newton greatly impacted Imperial’s development. Operating out of his Chicago showroom, Newton was fast becoming a major player in the glassware business. With his instinct for marketing and his awareness of consumer buying trends, he enabled Imperial to continue its upward path. Due to the popularity of imitation cut glassware, Imperial introduced a new variation called “NUCUT” in 1911. It expanded its iridescent line in 1912 with the introduction of “NUART” that included lampshades, vases, and decorative plates. The company’s third trademark, the “Imperial Iron Cross,” surfaced in 1913 and first appeared on the No. 582 Fancy Colonial pattern, an open stock line. To further enhance Imperial’s reputation and market penetration, in 1916 Newton doubled the size of his showroom in Chicago. The marketing of Imperial glassware became ever more ambitious. Working hand in hand with his talented marketing team, Wicke was determined to see that Imperial remained one of the largest glass manufacturers in the country.

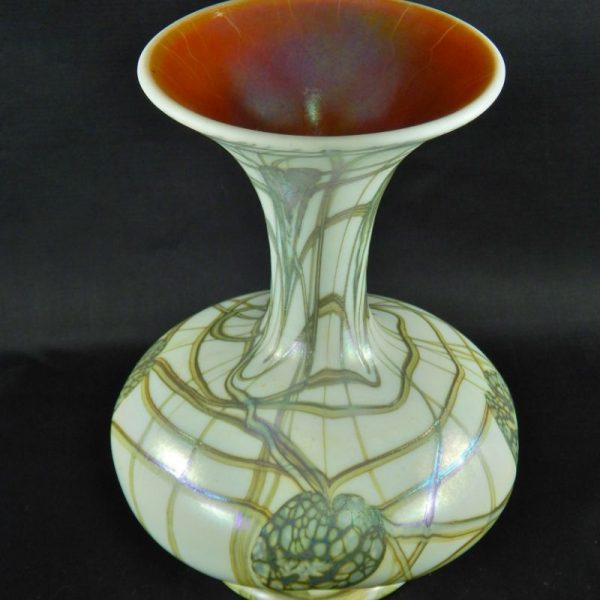

In the 1920’s, Imperial was confident of its ability to build on its past success. It continued production of its iridescent ware and added more colored glassware items. Some of these colored glass lines were the forerunners of the inexpensive colored glassware that gained popularity in the late 1920s and 1930s—later known as “depression glass.” In mid-1923, Wicke brought in a team of glass artisans who specialized in art glass. These men set about creating vases and fancy glassware, much of which sported an iridescent finish. Imperial called this line Free Hand. Imperial suggested in advertising to buyers, “Why go to Europe?” when they could purchase this high quality fancy ware plus regular stock from one source within the U.S.A. Unfortunately, the high prices of Free Hand, although competitive, negatively impacted sales. In 1924, Imperial attempted to duplicate the beauty of Free Hand with its moulded and less expensive “Lead Lustre” line. This line was arguably artistically pleasing, but it too was financially unsuccessful. In the early 1930s, barrels of unsold Free Hand remained stored at the factory. Some reported that entire barrels of it sold for one dollar apiece during the Great Depression. Without question, those of that era nearly 100 years ago would be shocked, as well as gratified, to learn how highly prized and valuable today’s collectors consider Free Hand and Lead Lustre to be!

Despite its earlier successes, Imperial approached the end of the 1920’s caught in the downward spiral that affected the country’s economy as a whole. The Stock Market crash on Wall Street in October 1929 was a huge blow, setting off a financial panic among investors and consumers alike. Then, less than two months later, Victor Wicke passed away. Imperial forged ahead without the man whose driving ambition was responsible for its rapid growth. At year’s end, Imperial faced a very uncertain future. Sadly, with the country plunged headlong into the depression, Imperial’s fortunes continued to sink.

Early in 1930, the board voted George Hannon as President, J. Morris Dubois (a long-time assistant to Wicke) as Vice-President, and J. Ralph Boyd as Secretary. In March 1931, nearly a quarter of a million dollars in the red and unable to pay its creditors, Imperial filed for protection through bankruptcy court. This action enabled the plant to continue operating. However, in July, the bankruptcy court stepped in, ordering Imperial’s remaining assets to be sold at public auction.

Try to imagine what was taking place in Bellaire that summer. IMPERIAL WAS GOING OUT OF BUSINESS! How could that be allowed to happen? It was a large employer; many in the area had either a family member or knew someone who worked at the “Big I.” Its closing would be a disaster for Bellaire and countless individuals and families. The events that followed truly reflected the spirit of Bellaire and the Imperial employees.

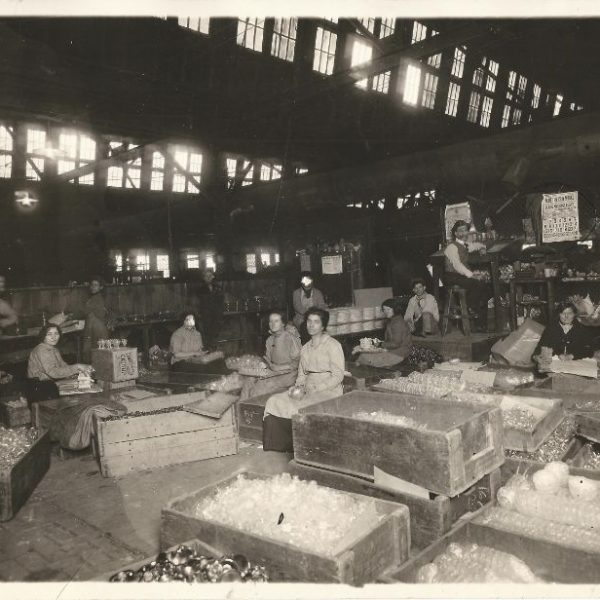

Through shrewd maneuvering, J. Ralph Boyd posted a $150,000 bond and secured the assets of Imperial. Reorganization followed, and with a new charter, the Imperial Glass Corporation arose. The new corporation then voted Earl Newton, the Chicago-based dynamic salesman, as its first president. This venture received remarkable support from Imperial’s employees. Cutting vacation time back to one week and pledging, in many cases, 10 to 20 percent of their earnings to the company, the workers of Imperial demonstrated their commitment to its future. Developments continued at a rapid pace. Creditors were convinced to accept stock in the new company as payment for past debts. With orders in hand, eighteen “shops” went to work for the new corporation. Boyd took over the day-to-day operation of the plant in Bellaire, and Newton remained in his Chicago office, devising plans to steer the company in a totally new direction.

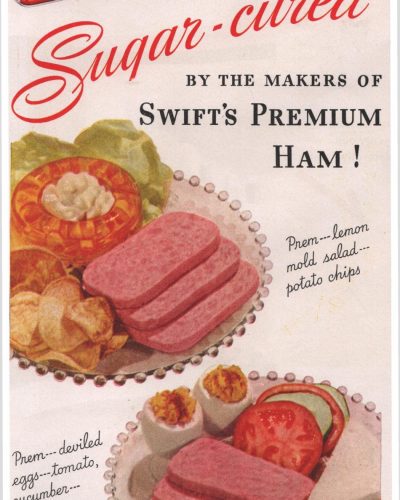

Legendary is the story of Newton’s meeting with the Quaker Oats Company and his securing a non-exclusive contract with it for Imperial. This contract initiated a major order for a glassware line to be used as “premium items” in Quaker Oats products. This new line became No. 160 Cape Cod. Imperial produced many barrels of glass in this line and shipped them to Chicago by the train carload!

Newton also established the Crown Glass Manufacturing Company as a wholly owned subsidiary. This short-lived venture received Imperial’s plain items and added decorations, especially cuttings, to them.

Newton then moved to capture a part of the high-end retail glass market. No longer restricted to the “Five and Dime” ware, Imperial attempted to compete head-on with the likes of Heisey, Cambridge, and Fostoria.

In 1932, Imperial’s future direction was altered once again with the arrival of Carl W. Gustkey as Executive Secretary of the Ohio Valley Industrial Corporation. Another important addition to the imperial family arrived in 1936. Carl Uhrmann, an Austrian who studied in Prague and earned degrees in glass making, provided the expertise needed to make the innovative new patterns Earl Newton had in mind. With the Depression coming to an end, consumer tastes were turning more toward clear crystal elegant glassware. With its new management team in place and large orders from new customers, Imperial wanted to move quickly to regain its former position in the trade. The only question remaining was how to go about doing it?

While on a visit to New York, Newton acquired a piece of glassware from the French Cannonball line. The piece, distinguished by a series of heavy glass ‘balls’ around it’s base, gave Newton an idea. What if the glass balls were made smaller and more delicate in nature? From some rough drawings, a few initial pieces were made. The new items led Newton think of the edging on the Colonial-style needlework called “candle wicking.” Imperial applied for patents, and it put the first series of items into production. Imperial’s No. 400 Candlewick was formally introduced at the Wheeling Centennial Celebration in August of 1936.

And the rest, as they say, is the stuff of history. Candlewick quickly became a mainstay in Imperial’s line-up of offerings, and it proved to be one of its strongest selling patterns. From some 40-odd items at the onset, the range of Candlewick items exceeded over 200 in the 1950’s. The elegant, clear crystal pieces readily lent themselves to a wide variety of etchings, cuttings, flashing, and colored pieces. With Candlewick, Imperial competed strongly with such popular lines as Fostoria’s “American” and Cambridge’s “Rose Point,” and it became Imperial’s most highly sought-after pattern. Although many other lines continued to be important to Imperial, Candlewick and Cape Cod were mainstays from their respective inceptions in the 1930s until Imperial’s closing in 1984.

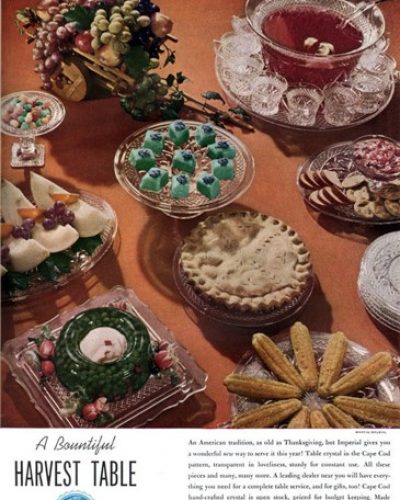

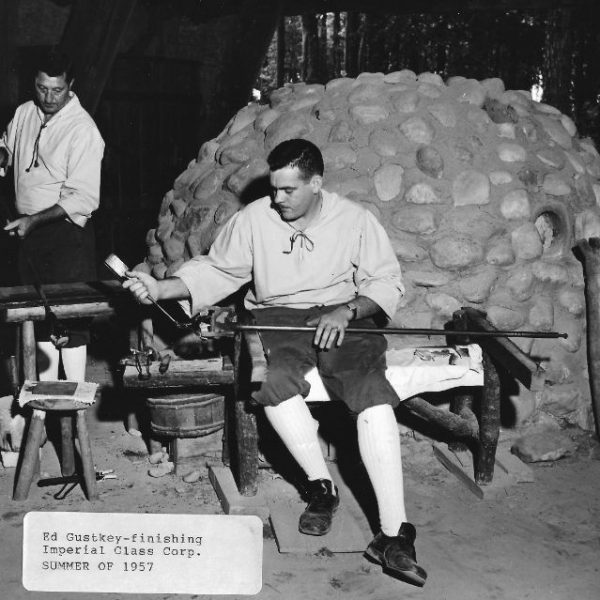

Unable to do justice to his dual responsibilities as President and Head of Sales, Newton resigned as President in 1940, passing the torch to Carl Gustkey. For the next 27 years, Gustkey’s business acumen and natural talent provided Imperial with strong and steady leadership. Gutskey had many major goals in mind. Among them, he wanted to expand Cape Cod and Candlewick into new markets, and he wanted to make Imperial a household name. To accomplish these goals, he took a new and different approach. In 1940, together with his close friend, D. Milton Gutman of the Gutman Advertising Agency in Wheeling, they conceived a strategy for an advertising campaign that promoted Imperial’s glassware directly to the homemaker through advertisements in major women’s magazines. The concept proved to be a huge success. The resulting popularity of Cape Cod and Candlewick, along with other patterns, enabled Imperial to remain strong during the World War 2 years.

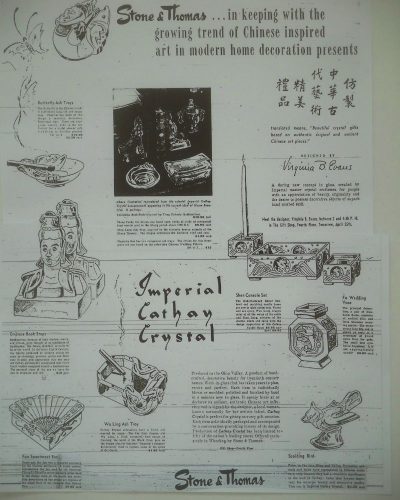

Following the World War 2 era, Cape Cod grew to nearly 200 items, and the Candlewick line continued to expand as well. In 1949, Imperial introduced its unique Cathay line and followed it the next year with the introduction of its Milk Glass line. Following patent approval, a new trademark appeared in 1951: an “I” superimposed over a “G.” This “IG” and the early “Iron Cross” proved to become two of Imperial’s most-recognizable trademarks.

The 1950s were, in large part, successful for Imperial, but as this decade drew to a close, ominous portents of change were looming. On the rise were costs for labor, raw materials, and energy. Further, consumer acceptance of machine-made glass combined with the growing popularity of less expensive foreign imports made for difficult times for the American handmade glass industry. In 1958, the A. H. Heisey Company of Newark, Ohio became a victim of these changes. Due to a long time friendship with T. Clarence Heisey, Gustkey was able arrange the purchase of Heisey’s equipment and moulds. In 1960, the same fate befell the Cambridge Glass Company of Cambridge, Ohio, and Imperial garnered its assets as well. Well aware of the challenges the industry faced, as well as the thinning ranks of its domestic competitors, Imperial hoped the 1960s would provide new openings for its glassware.

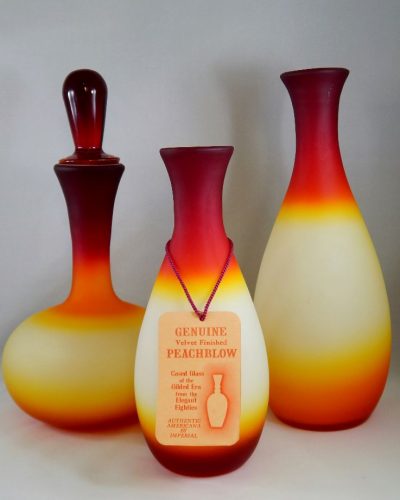

In the early 1960s, Imperial’s new Slag Glass items quickly became an industry standard for their beauty and quality. Imperial then marketed a line of Peachblow vases that brought to consumers a taste Wheeling Peachblow from the 1880s. A revival of some of Imperial’s original patterns appeared. Called ”New Carnival” and “Collectors Crystal,” Imperial produced these items using the moulds of some of the old NUCUT and Iridescent ware so popular some fifty years earlier. Imperial formulated new and unique colors as it also expanded its offering of decorated items.

Unfortunately, Imperial suffered a tragic blow in 1967 as President Carl Gustkey passed away on October 26. On December 7, Imperial’s Board of Directors elected Executive Vice President Carl Uhrmann to succeed Mr. Gustkey as President and General Manager. Over the next few years, foreign competition and a deteriorating economy had a deleterious effect on Imperial’s ability to stay afloat. Imperial stock-holders, unwilling to face yet another bankruptcy, decided in December 1972 to sell the company to Lenox, Inc. of New Jersey. Mr. Uhrmann was largely responsible for the Lenox acquisition that resulted in a positive gain in stock value and benefited many residents of Bellaire.

A major reorganization in management and marketing approach quickly ensued. Lenox wanted to use its new subsidiary to target the highly competitive crystal giftware business and to complement its china lines. However, even with the implementation of new concepts and infusion of capital, Imperial’s decline continued. With each passing year, the work force dwindled. By early 1981, the largest handmade glass house in the country had become a shadow of it’s former self. The Bellaire community feared the plant would close.

In May 1981, Lenox elected to sell its Imperial subsidiary to Arthur Lorch, a New York investor. He announced plans to turn Imperial into an exclusive handcrafted glasshouse, marketing specialized items based on the company’s original lines. This model meant that the huge plant would be reduced to making limited production items based on sporadic orders from customers. Lorch’s lack of experience in the handmade glass industry and his ill-conceived marketing plan quickly spelled doom for Imperial. By the fall of 1982, foreclosure seemed imminent. Lorch’s precarious position resulted in his asking the remaining employees to accept a reduction in wages. The ensuing strike by the Glassworkers Union forced Lorch to sell to Robert Stahl, a Minneapolis investor.

Forced back into bankruptcy and under the provision of Chapter 11, a skeleton crew was allowed to continue operation. In August 1984, Imperial filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy. The once great Imperial Glass Corporation passed into history. Due to the many ownership changes in its last years, many parts of the Imperial’s history are lost forever.

One might assume that with the razing of the old Imperial factory building in July of 1995, we would have reached the conclusion of Imperial’s story. Today, a modern shopping plaza exists in its former footprint. But the memories of what once stood there and the many people that made it work, be they management or skilled workers, remain. Collectors everywhere continue to collect Imperial’s glassware and study Imperial’s history.

The National Imperial Glass Collectors’ Society, having grown from a handful of people in 1976 to a membership of several hundred today, continues to find ways of preserving Imperial’s legacy. In most years, the Society holds it Annual Convention in St. Clairsville and Bellaire, Ohio, bringing together those who desire to share their love of Imperial Glass. In doing so, the life of the “Big I” lives on. In 2003, the Society accomplished a longtime goal with the establishment of the National Imperial Glass Museum, 3200 Belmont Street, Bellaire, Ohio. It is dedicated to preserving the history of the Imperial Glass Corporation, paying tribute to its employees, educating the public, and providing research opportunities.

Design & product history

Marketing History

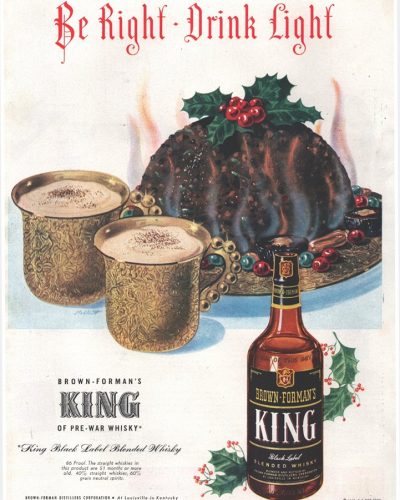

Imperial marketed its glass products through trade shows, marketing sales representatives, advertisements, and other means. Imperial published advertising in a variety of ways – catalogs, brochures, trade journals, point of purchase advertising, and direct consumer ads in magazines and newspapers. Imperial glass was frequently featured by other companies in advertising their products.